Back to the Reader Stories landing page

Welcome to the second issue in Season One of The Cure for Sleep: Stories From (& Beyond) the Book which you can read in full over on my free Substack. This month’s invitation to write concerns memory games: subscribers were invited to consider the loss of loved ones through the things they had around them. All responses are curated below.

As I sit here thinking about my own experiences of losing someone, I remember…

AMy millios

Blips and beeps and bells from the other side of the ICU curtain mixed with feet scuffling and squeaking across the floor. He was gone really the moment the aneurism broke free, but his heart was still beating at an incredible clip; strong; a steady green line on the monitor, here and gone all at once. I wiped a drop of blood from the corner of his mouth, and as the sun rose and my grandfather Stanley lay dying I held his hand. I noted its squareness, thick knuckles, traced the gold band he’d worn for over 50 years, and I saw it for the first time: his hands were mine. Hands that held four children and grandchildren, and one great grandchild. That roasted lemon-stuffed chickens basted with olive oil and oregano over campfires. Fingers that tied flies before palms cast out over the water. Hands that planted two gardens of vegetables every growing season, watered, pruned, picked shiny green peppers. Other than photos I do not possess any objects treasured by him. He was buried with the compass he used to navigate forests, and I’ve no idea what became of his walking stick. But do I have his hands. My hands are the objects. My hands are the treasure.

My Brother Mike

*

He was gone within 27 hours. There was no warning. It was a sunny evening, he was playing football, there had been no rain for weeks and the pitch was hard. We hadn’t shared a home for 10 years so there were few mementoes. Just some gifts from over the years but we were so young, I was left with more memories than things. All tinged with sadness. I looked for him in the streets where we met, gazed at the paintings he loved, listened for his voice at my side as I strode the hills or plunged into the Atlantic. Sometimes he visited my dreams and we talked. Often it was that he had survived the accident but his life had changed.

*

The years passed. I held him close and kept going. I gave birth to my first child at the age at which he had died. My children had reached early adulthood when tragedy began to enter their lives. I started to think carefully about when, at a similar age, my own world had disintegrated and how memories of a wonderful life were shaped by sadness.

*

Now I found his beautiful voice on reel to reel tapes, loving letters in his exquisite script and photos of our childhood that, for three decades, had been too painful to revisit. I recorded interviews with my sisters, my mum, his friends, his son and we talked about how good he made us feel, protected and challenged and joyful, so alive. So alive. Even still. You never forget how someone makes you feel.

*

That summer a radio documentary I made about memory and Mike was broadcast. Some weeks later I was having a massage, a birthday gift from my kids. As I lay in the silent, still room a slight breeze glided across my bare legs and chimes suspended from the ceiling tinkled in an unexpected way. Afterwards the masseuse told me that we had had a visitor. A man. He had asked her to let me know that he was good and doing well and to say thank you.

Sheila De Courcy

My Mother

*

It was as if she was passing on a baton; a rich purple lidded tube that must one day have been handed to her and was now being handed to me. She ‘thought I might like it’.

*

My home has always been full of my parents, from the box of his tools Dad put together for me that first Christmas I was married to the king-size patchwork bedspread Mum made by hand when she had retired from teaching. Each patch is a memory from the clothes they wore to furnishing I recognised; a family heirloom. The tools in our house now are always mummy’s tools, though first they were Dad’s, including the old tobacco tins full of nails and screws.

*

Most of the items of theirs that I possess are of practical use whether made or passed on but this was different. Inside the tube were a number of papers. Looking at them now, I seem to be looking at another life, separate from mine, yet like a pattern I am following. The first is her General School certificate, dated 1936, from Raine’s Foundation School for Girls, a Jewish School to which my mother won a scholarship in 1929. Her time as a scholarship ‘gentile’ is well known to me: Coming from a poor East London home, her attendance and success there, despite some of its traumas, impressive. However it was the range of subjects she passed that struck me. English subjects, yes, but written and oral French and German too. Mathematics I knew she excelled in, but Inorganic Chemistry, Magnetism and Electricity? Art: elements of colour and design, model drawing and freehand. And singing. Suddenly I seemed to recognize threads of belonging, interests shared over years becoming part of me.

*

When I look at them now, I imagine her going to school in her second-hand uniform; her nights studying in their tiny damp terrace house, practising the violin my grandmother detested; looking after her brother while her mother washed doorsteps for a living.

*

Another paper in the tube has a job application letter drafted on the back: ‘I have wanted to be a teacher since I was eight’. Eight; the age she was when her father died of cancer in a mental asylum. I resisted teaching but it was in my genes and I loved it once I started. I recognize those genes in my own daughter now she too is about to begin that process.

*

Only one paper is in colour: Moray House College of Education, Edinburgh, 21st June 1962. She was awarded an education diploma with merit which at last enabled her to pursue the teaching life for which she had longed. I was eight. Despite my resistance to the career I later came to love, I treasure the days I was able to go into school with Mum. The children loved her and flourished under her diligent care. To them, I was ‘Mrs Stewart’s little girl’, although I was twice their age. Sometimes I wonder if there is some kind of mycorrhizal network that ran between us, constantly building connections that fed into my life, nurturing me like Suzanne Simard’s mother trees. I am obsessed with colour, had a challenging school life, belong to a choir, studied maths to A level, became a teacher and create patchwork in a small way.

*

The papers in my mother’s ‘baton’ are a glimpse of a life lived until hers had run its course. What has passed into my life is infinitely richer and still nourishes through objects and memories.

Jean Wilson

My Great Grandmother, Amy

*

The story we grew up with was passed on to me by my father, strangely, not my mother, her grand daughter. She, Amy, had been in service and fallen prey to the attentions of the master, or his son, or someone, anyone, and had become pregnant. Because of this, she was locked away in the crazy house until she died, nameless and forgotten. It’s what happened to unmarried women then, just one of those Victorian things.

*

Thirty years later, my work on our family tree uncovered a different story. My great grandmother was feeble-minded, deaf and dumb, and also a scholar, depending on which census you read. She had worked at the local mill with everyone else, lodged with various family members in a succession of tiny tied-cottages, swapping about here and there, weavers all the way down. The birth certificate named a father I could not trace, a name made up to save face no doubt, but she looked after her only child until he went to fight in the French trenches.

*

It wasn’t until she was forty-one that they took her away, just as they had taken her mother and her sister to a different asylum, the reasons unknown or concealed. She died inside that place after forty-six winters, in the spring following the birth of my sister; they could have met, but my mother didn’t know about her grandmother then, and realised only years later that she must have been ‘the old lady’ that her parents went to visit ‘in hospital’ on occasion.

*

My sister’s own daughter bears her name.

Sally Harrop

Dad’s Home

*

It was a beautiful hot day in August. Kilkee was sparkling and the heat had drawn people to the beach and pollock holes. That was the last time I saw my Dad. When he dived into the water our connection on this earth was broken. We came back to Dublin, my Mother and I, and it was to a house where his presence or lack of was

thick in the air.

*

At first his suites hung like lonely vessels waiting to be filled with his being. I kept his shirt for quite a while. I would hold it to my face and breath in his essence. As long as his smell still lingered he was somehow near. Letting go was not possible, he would be back. After The Vincent De Paul charity collectors had come and gone, and the shirts were no longer there, I waited.*

My Dad the medical Rep must be on the road. His Hillman Hunter taking him to unknown places where weekends with us had been interrupted. At home there were copper and brass objects waiting to shine. Treasures he found in junk shops which he would spend hours polishing now leaning against the garage wall, green and sad a bit like us.*

Yes that was our house: waiting, people, cats and copper. Most nights I lay in the dark knowing it would not happen, but believing it could; waiting for the sound of the White Hillman Hunter, willing it. The headlights turning into our driveway lighting up the garage door. Dads home. When the hard solid block of reality seeped slowly in I knew those lights would never shine again and I began my time of grief.

Louise Newman

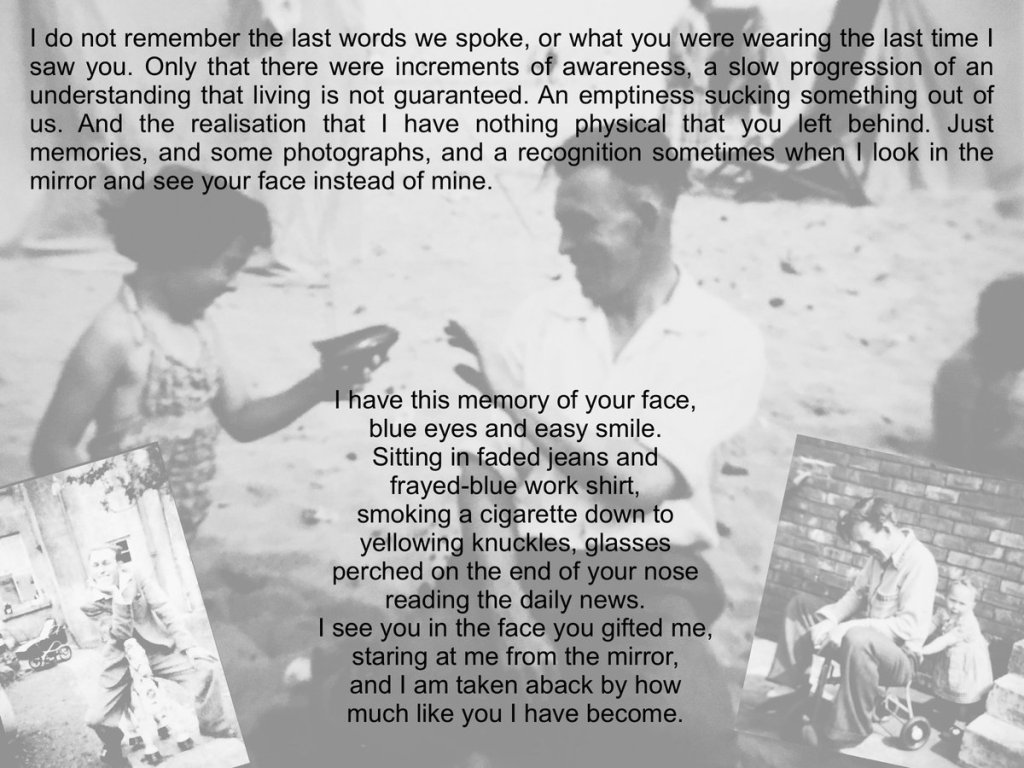

In Sepia

*

The 3D you is a sepia photograph now. Colours faded. I squeeze my eyes tight in a bid to bring you back to life, channelling Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz. The edges are fuzzy, and I can just about make out the crinkles around your eyes. I can’t see your hands or the shape of your body in your red jumper anymore.

It is smell and sound that sharpen the lens a little. That red jumper now sits amongst my own in the wardrobe. I inhale it, but your scent has dissipated and mingled with mine long ago.

There is just one drawer I can open, though. Your old bedside table sits in the hallway, which I filled with ‘Dad’ things: a hammer, spirit level, screwdrivers and alum keys. And it is here where the last molecules remain of a life once lived: a faint whiff of tobacco and the sweet woody mustiness of you. The catchy piano chords, the snap of drumbeats, and the line ‘put a pony in me pocket, I’ll get the suitcase from the van’ take me back to the sound of you laughing. An uncontrollable belly laugh that I rarely saw. I see you slapping your thigh with tears running down your face saying, ‘Bleedin’ wrap up’ or ‘Sod my old boots.’ Never mind the Only Fools and Horses catchphrases; you had your own.

vanessa wright

The messiest corner of our study contains several piles of my Russian family photos.

Some hold happy memories, others – just memories or the absence of them.

There is a photo in that pile that unsettles me. It is black and white and slightly yellowed from age. There is a brief handwritten note on the back: Moscow, 22 August 1970. The day of my parents’ wedding.

It shows eleven people standing in a haphazard line against a lightly coloured and totally blank wall. You don’t need to understand much about photography to see that it was taken by an amateur and with little care for future memories. There is a certain awkwardness about this photo – in fact every detail of it reveals clumsiness and unease. Most people in the photograph are staring into space with a frozen expression of indifference. Only my mum looks radiantly happy and beautiful in the photo, as beautiful as she always looked in all her photographs taken before that day… but never after.

To the right of my mum is dad. Their arms barely touching. He is dressed in a suit and tie, probably the same one he wears to work every day. He is gazing across the room and straight through the camera.

For reasons I can only guess, my grandmother is not in the picture but what I do know for sure is that I’m in that photo. Yet invisible to anyone, I can see myself in my mum’s shining happiness that looks so out of place on that fading grey background.

elena

My hair hangs heavy like wet rope as I sit in the faded green bath – always run too shallow so that my toes become hierarchical islands in a sea without a tide as an Imperial Leather soap-boat bobs by.

Lucy lichen

My teeth chatter not because I’m cold but because it’s part of the game and I like how it makes her care.

‘Hair, face, feet and peach?’ She asks, and I giggle as I clamber over the side, rewarding her with a toothy grin as my answer. A large terracotta towel quickly shrouds my squirming body and as she feeds my joy with requests of ‘quick, quick, quick’ the towels are always rough and I jump like a fish on the line.

I escape to streak down the stairs leaving tiny wet toes on the carpet. I round the corner into the living room like a whippet.

‘Cor blimey maid, you only just made it away from that towel this time,’ and he pats to the chair but he doesn’t need to. I place myself neatly between him and the arm whilst he wrestles an old blanket from behind him and around my naked body.

‘Can I have some?’ I ask, pointing to a big bottle of cider stashed next to him. His scuffed red cheeks swell with naughtiness.

‘You bugger! You’m just like ya ol’grandad!’ And he begins to sing drink up the cider whilst I’m thrown around on his knee, laughing from my belly. The creak of my nan’s footsteps sound and he puts his fingers to his lips which I copy whilst he gestures upstairs with his eyes.

After a while the fire begins to speak ‘weeeeeee pop‘ and it sets off a small ember that lands on the cat’s ear. She hisses and glowers but remains sitting feet curled under bib. I don’t like it and look to my grandad but he’s laughing at the TV, he can’t always be there I suppose and I don’t like that either. The fire speaks again ‘weeeeeee‘ but no pop, just suspense and I’m even more anxious waiting for the moment to break, waiting for the spark and the hiss but nothing comes.

I fiddle with a familiar loose thread on the seam of the chair running it through my fingers as it catches on the edges of my bitten nails. Tomorrow I will have to go home and I think about that as – without any effort at all – the thread gives way into my hand and I’m scared its all going to come undone.

My Grandma

sheila Knell

She was born in 1929 in Liverpool and said her name – Mavis – came from a singing bird.

She won the All-England medal for dancing at the Albert Hall, age seven. She sang and danced to ‘You Are My Lucky Star’.

Hitler invaded Poland and Prime Minister Chamberlain finally recognised appeasement would not work, declared war on Germany, resigned and died shortly after. Liverpool was bombed for the first time on August 17, 1940.

She spent nights alone in a brick house with a slate roof and blackout curtains. Over 4000 people died, second only to London.

She practiced wearing her gas mask at school. She remembers weekly rations of two ounces of tea, two ounces of butter and one egg, but typically only powdered eggs were available.

She married an American GI in 1945 and the marriage certificate listed her as a spinster at age 16. Her husband was 8 years older than her and brought his war bride to the states in 1946 and unleashed years of cruelty.

She gave birth to a baby who died 7 months later and then to my mom in 1949. Her divorce was finalized in 1955. She remarried in 1956 and had a son. When she found her brother again after forty-four years he was still mad at her for not coming back home. She never acknowledged that this could have saved a lot of pain in our family. He never acknowledged that it would have been hard for her to come home. She never changed her citizenship. In 1988 Father O’Connor was informed by the bishop that the first marriage annulment was approved – ‘was null from the beginning’ in fact – and charged her $150: she and her husband could then take communion.

Her embroidery was nearly as good on the back as the front, neat, tight stitches.

I once gave her a list of questions. She said the happiest day of her life was when her mom left England to come to the States to be with her. The other answers were all about the regret of giving up her dancing career to come to America.

These are the questions she skipped: what people don’t know about you, what’s most important, advice for other women in the family, describe a perfect day, worst piece of advice you ever gave, dream vacation, something you are sorry for.

She would have denied being depressed, at most admitting to being melancholy at Christmas. She kept a tight grip. She said her heart was like a hotel, there was room for everyone, but that was a past life.

Her best years were over by age 16.

Memory Game

andrea day

Flick over one image, then the pair. Flick another… no, not a match. Try again, come on, get on with it. Remember, for goodness sake, there’s only a few pairs. Only a few pairs, only a few photos, only a few years, then five years, ten years, twenty, thirty. I flicked over his image. It was faded. Itss match would also be torn and ragged, if I had one. His face smiled out at me, his youthful magic was an inward breath that never came out. It was any ordinary day. With some of our breaths we’d laughed at normal things, silly things, things that are importantly not important and then we’d said goodbye. The next caller to speak his name asked I sit down. The primal wail escaped my body and frightened my soul. No, it isn’t true. It couldn’t be true. I didn’t want it to be true. But, then it came, an explosion deep in my heart. My chest clamped a lock, but sparked a fire that melted rock which flowed deeply beneath, buried as lava set. If I hung up instantly I could make it not true. I knew I could. But I couldn’t. I couldn’t turn back time. For days, then weeks then months I sobbed the loss of never again. I screamed the ache of fragile memories. Tears tore at my throat, my eyes bulged to peer into the mist of fading light, with his fading face. My heart carried on, my breath it steadied. My feet dragged through the daily grind of a thick black quagmire. Seasons cycled, stars winked the moon and the sun parched us all. New love was tendered, bells rang and golden rings exchanged with promises. Children came and learnt the game. Match the pairs, count them all.

I’m sat in the middle of the floor, surrounded by bright worms of yarn. Squiggles of orange, blue and green hang from my pyjamas, as I stare out the window – agitation spooling tightly around my limbs.

Lauren longshaw

Such a waste.

I brush the lazy dangles from my legs, force myself up and go and admire my latest creation. It hangs perfectly on the antique wooden frame. Its Knots of finality and precision chopped ends fill me with satisfaction, yet the yarn on the carpet fills me with indecision and apprehension.

I google yarn scraps and find patterns to use them up on.

Happy that they will have their use at a future date, I grab a bag and start scooping up the rainbow worms and stuffing them into the bag.

When the floor is clear I take the bag and store it neatly in a drawer. The agitation starts to unspool.

I open the drawer above and pull out the neatly stacked piles of papers. I take them to the kitchen counter, lick my fingers and flick through. Water bills, work rotas, and rogue birthday cards that should be with the others, in the box under the bed. I pile them together, knocking the sturdy bottoms on the counter, to make them as uniform as I can. A small shower of synthetic glitter speckle the counter top. I sigh and tear off a kitchen roll square to wipe it clean.

I’m about to store the papers away again when I spot the shopping list.

Milk

Bread

Potatoes

Tobacco

Yeast

A short list, written in her small, precise handwriting.

I feel the memory in my stomach, a churn, then a tightening, like a fisted hand gripping tight. I recall the day. Being at work and seeing the dozens of missed calls. The hazy disbelief in my mum’s eyes.

A couple of days later, going to her house to sort, I remember her routines, through the remnants left. Piecing together the very last of her days with the evidence of activity about the house.

The pan on the hob, filled with thick brown stew and sagging dumplings – Tupperware boxes laid out, waiting to be filled.

Her bag and scarf stationed near the front door, ready to adorn her for her trip on the bus.

I look in the freezer and gulp down tears as I see the homemade bread rolls, frozen solid in cellophane bags. I see her rough hands kneading with fervour, a floury cloud dusting the kitchen, as she pulls, pushes and shapes her doughy creation into a smooth, supple ball, ready to be placed on top of the fireplace.

The living room table holds a coffee-stained cup, a biro pen and – underneath it – the handwritten shopping list.

I take the shopping list and the frozen bread rolls home with me.

Sitting here now, I drop the cards into a messy pile in the drawer, forget about the yarn scraps, grab my bag and scarf and escape out the door.

Maybe I’ll use up the scraps, maybe I won’t. Either way, their purpose will be woven eventually.

‘My job was to paint their eyes blue,’ Pop once told me when I was a child.

Corinne Kagan

I imagined him going from house to house, crouching down in front of television screens and delicately painting the irises on the faces as they appeared. I thought that made him a hero. But of course, he’d become a hero long before then.

He was blown off three ships in the war and branded a jinx, even after rescuing his captain. When they washed up on the shores of Italy with no idea whose flag waved beyond the beach, my pop waved down a military vehicle only to find it was being driven by a chap he’d known from school. I think his luck took a turn from there.

Of course, I didn’t hear these stories from him, they were shared after he was gone. He wasn’t much of a storyteller, in fact, he rarely spoke to me at all. But it wasn’t his words that mattered to me as a child. It was his presence. The feeling of safety when he pulled me onto his lap as he did a crossword, and the smell of humbugs and pipe smoke that emanated from his scratchy woollen jumpers. Those gentle long fingers. Fingers that painted and gardened and crafted and mended. We used to call him Jim’ll fix it. Although you can’t say that anymore.

That minty tobacco smell has followed me across the world, appearing only in my darkest moments. Always a reminder of the best love I’ve ever known. A love that was unconditional and uncomplicated. I think I’ve spent my whole life searching for that same tenderness because feelings don’t fade like faces do.

In the care home, the faint ammonia tang of urine mingled with sharp disinfectant and the heavy sweetness of an air freshener. Grandpa sat in an armchair by the window, gazing out. His sharper edges worn away by age and memory loss, he showed us every card he had been sent with boyish pleasure. Then he patted my pregnant belly and squeezed my fingers tightly in his cool, dry hand.

Eight decades before, his own mother had died in the grip of childbirth, stolen away from him along with a younger sister who was never named. With them, his own childhood died too. His father, unable to keep the children at home, sent all three to an orphanage where strange men preyed on the children at night and Christmas brought the heady excitement of a single orange. Grandpa always insisted that his father’s monthly visits had protected him from the worst abuses. He had merely lain in bed and listened to the other boys praying to be spared.

Afterwards, these scars ingrained a deep sense of shame in him. He would apologise for his failures in business, his lack of ambition, although he built a house and supported three children of his own. ‘I always felt myself to be more of a family man,’ he would say, by way of explanation. He seemed not to realise what a soaring accomplishment this was, after a childhood so emptied of love. Or how touching his appreciation of small blessings.

Someone had dropped by before our visit, bringing with them a tin of anchovies. Such a sharp, pungent flavour of flesh and salt compared to the bland food offered by the home. Grandpa was overjoyed with them and, as if we might not believe him, insisted on leading us to the kitchen. A carer produced the fish as requested: a half empty Tupperware of small, limp fillets, swimming in a silky brine. He beamed at us, held them out reverently so we could look, then clipped the lid carefully back on and tucked them into the fridge, ‘for later.’

Adela Ryle

I never knew him – how could I?

larissa reid

He died in 1927, my great-grandfather – his daughter, my grandmother, was just 9 years old. And yet. I ‘know’ him a little, through one photograph, a couple of stories – my grandmother as a tiny child out in India, bounced on his knee, taught a song about a bunny rabbit. His role as an army band master, conductor, bugle-player; instrument swapped for bayonet when it came to war. My grandmother, born in Peshawar, now Pakistan, 1917. My great-grandfather, Alexander Uriah – or Uri, as he was known – died of stomach cancer in 1927, back home in southern England. He was handsome, he stands proud in his photograph in my study now, army uniform, hint of a smile, hint of a wicked sense of humour. A tough life: his own mother died when he was a youngster, not even 10 years old. Landed in a poor house with several of his many siblings. Disappears from the records and reappears in the army years later, his birthdate wrong and I have a sneaking suspicion that he lied to get in there… all this, I know as fact. Anything more, I create. His love of music, the way his world moved in time to rhythm and pace and the way he closed his eyes to listen. The long, long boat journeys to India and back again, repeatedly. His eldest son following in his footsteps, his little girl jiggled on his knee whenever he had the time. She remembered his twinkling eyes, his warm smile, his fingers beating time as he sang. This is what I hold in his photograph, while his Edwardian-era eyes gaze back at me.

When my Grandma died, I was given two of her cookbooks. One is the 1950 Betty Crocker’s Picture Cookbook. On the page with Filled Bar Cookies, she’d written ‘delicious’ in her distinctive joined-up writing. For Thumbprint Cookies, she wrote: ‘Added ½ cup nuts + 4 chocolate chips in each thumbprint. Delicious! X mas ‘80.’

wendy knerr

In the other cookbook, Grandma made corrections – for instance, for Homemade American-Style Noodles, she noted that the tablespoon of salt should be a teaspoon. When I flip through the book now, I spot other pen markings and realise that these were made by me. It’s where I converted cup measures to weight, which I did after moving from the US to the UK. When I see my own marks, I feel a catch in my throat – am I ruining Grandma’s cookbook? Should I be keeping it as she had it, to remind me of her?

‘Oh honey,’ I think she would say, ‘it’s not the Bible. It’s just a cookbook.’ (Also, it’s important to use a teaspoon rather than a tablespoon of salt in that noodle recipe!). But I want to hold on to what was hers – what was of her. On the one hand, I don’t want her things to sit in a box and not be appreciated; but as I use them, I change them. I’m wearing out the leather band of her delicate watch. I’ve torn and then mended her apron. And I’m marking up her cookbooks. As I use her things, it can feel like she’s slipping away. But maybe, instead, this is even better than just having a box of heirlooms, of things that never change. Maybe we merge, a little bit of her and a little of me, when I make use of her things.

I’ve came to visit grandfather straight from work. In the small damp room we ate a dry lemon cake.

Victor milesan

He asked how am I doing in school.

I’m coming to you straight from the office, they pay me good. I’m grown up now. I’ve recently bought a nice phone, you could use one too, we could talk more often maybe. I’ve passed to him shiny-metal Nokia cellphone, evidence of present (or the future) he forgot. He grasped it clumsily, and held. Upside down, nodding. Nice, nice. And this camera of yours, I’ve had similar. He changed the topic, pointing to black Pentacon BC1 I’ve brought about everywhere.

Yes, it’s a nice one, automatic. I’ve bragged. We should take a picture of ourselves, now, there is a timer. I’ve put it on the mantle, set the timer and sat next to him.

Silent; nice, nice. I’ve made pictures as well back then. Bring this photo next time. I will take out my old photos from the basement. He pushed small change into my hand, forgetting I was not a child anymore.

We see each other soon.

I never did. What’s the point in embarrassing myself. Going in circles. That’s cruel, redundant, weak. He will forget anyway.

He is not there any more. Straight from work I’ve come to the small damp room. On a dusty mantle, old photo of a child and man, us, basking in the sun.

Grandpa’s table

rosemary kirkus

As I write, my fingers pause, tracing the blackened carving around the edge of this solid oak table; darkened by years of smoky coal dust and the residue from our foul-smelling oil heater. My young hands once fingered the same curves as my elderly hands do now, the same way Grandpa’s did.

Here he presided over Sunday lunch with a formality belonging to the Victorian age into which he was born. The sharpened, polished silver carving knife poised to slice the Sunday joint.

Few photographs remain. Grandpa was a photographer in a world before selfies, an automobile engineer in a world before motorways.

Bathrooms had to be white and music, classical.

A kindly, honest man who loved dogs, running over fells and swimming in mountain pools. He also loved Tony Hancock and chuckled heartily for half an hour every week.

By the time I knew him, he spent most of his time sitting quietly by the fire, tinkering with his old crystal wireless set.

I can feel the tickle of his moustache as I kissed him goodnight, the touch of his bony fingers holding me as we posed for a photograph.

‘Little Rainbow Girl’ he called me in a rare moment of affection.

We didn’t talk much, my grandpa and me. He was locked into his deafness as I was locked into my shyness.

This quiet old man had lost a brother, three sons, his money and his business. He held his grief tightly inside.

One day Grandpa disappeared upstairs to his bedroom, a few weeks later he disappeared into hospital and shortly after that he disappeared from the world completely.

‘Don’t worry darling, nothing has changed,’ said my mother. Strange epitaph.

My grandpa had gone but still my fingers stroke his table with love.